The UK Constitution

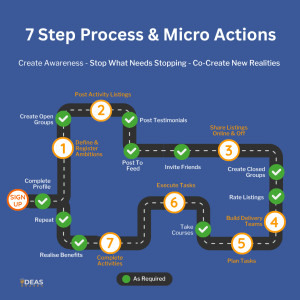

Ambition & Activity Detail

The UK Constitution: From Equal Protection to Political Distortion

For centuries, the British constitutional system operated on a remarkably simple — yet powerful — foundation: all citizens were equal under the law.

This principle, deeply rooted in the Magna Carta (1215) and later cemented through common law tradition, underpinned the UK’s reputation for fairness, justice, and stability.

Though the UK has no single codified constitution, it relied on an intricate blend of statute law, common law, and constitutional conventions. This allowed flexibility and continuity. Key elements like parliamentary sovereignty, the rule of law, individual rights, and equal treatment were assumed — and protected.

But much has changed.

What Happened?

Over the past few decades, particularly under the Labour governments from 1997 to 2010, significant constitutional reforms were introduced. While some changes had merit — such as modernising elements of the state — others reconfigured the balance of rights, law, and representation, often without deep public debate.

Let’s examine the impact of these key changes:

1. Devolution and the Fragmentation of the Union

The Scotland Act 1998, Government of Wales Act 1998, and Northern Ireland Act 1998 effectively created regional parliaments and assemblies, granting significant law-making powers.

Impact:

>>> England was left without a dedicated parliament or assembly.

>>> Citizens in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland gained additional layers of representation and legal recourse.

>>> The “West Lothian question” emerged: Why can Scottish MPs vote on English matters, but not vice versa?

This disrupted the principle of equal legislative impact for all UK citizens.

2. The Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA)

This act incorporated the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) into UK law, allowing UK courts to hear human rights cases directly.

Impact:

>>> On paper, it increased access to justice.

>>> In practice, it created legal avenues that increasingly favour specific minority groups over the democratic will of the majority.

>>> Judicial activism rose — unelected judges began to shape national policy under the guise of “rights”.

Many argue this shifted power from Parliament to the judiciary, weakening democratic accountability.

3. Judicial Reforms and the Rise of the Supreme Court

The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 removed the Lord Chancellor’s judicial functions and created the UK Supreme Court in 2009, severing the House of Lords’ final legal authority.

Impact:

>>> Symbolised a separation of powers — but also politicised the judiciary.

>>> Judges began issuing rulings on immigration, deportation, and free speech that contradicted majority sentiment or Parliamentary intent.

This further eroded the feeling of equal access and shared legal norms.

4. Mass Immigration and the Politicisation of Identity

Post-1997, immigration policy shifted dramatically. Under Labour, net migration rose sharply, and multiculturalism became an institutional doctrine.

Impact:

>>> Legal exceptions and protections were tailored to identity groups, eroding the idea that all citizens should be treated equally under the law.

>>> “Hate crime” laws disproportionately protect certain demographics.

>>> In practice, free speech is no longer equal — criticism of some groups is criminalised while criticism of others is celebrated.

This undermines constitutional neutrality and legal impartiality.

5. Loss of Accountability and Representative Integrity

Labour’s use of quangos, expansion of the unelected civil service, and manipulation of electoral systems (e.g., introducing PR in devolved nations but not Westminster) further diluted equality.

Impact:

>>> Ordinary citizens have less influence than elite technocrats or special interest groups.

>>> Power is increasingly centralised, but no longer accountable to the people through direct democratic checks.

The constitution was never meant to protect elites at the expense of the public.

Where We Are Now

The original principles of the UK constitution — flexibility, equal justice, sovereignty, and democratic representation — have been reengineered.

Now we have:

>>> A fragmented legal system based on geography, identity, and activism.

>>> Unelected bodies with more influence than elected MPs.

>>> Courts that reinterpret law in ways that contradict the people’s will.

>>> Citizens treated differently based on who they are, not what they do.

This is not progress — it’s a quiet constitutional coup, executed in increments, often without public consent.

Questions for Consideration

>>> Can the UK still claim all citizens are equal under the law?

>>> Has judicial power become a substitute for democratic process?

>>> Is the UK still one country, or a set of unequal regions with different rules?

>>> Can we restore the balance between rights and responsibilities, power and accountability, law and justice?

The Call to Action

We must revisit and debate the nature of our constitution — openly and honestly.

We need:

>>> A codified constitution, approved by referendum.

>>> Legal reform to reinstate equality before the law.

>>> A recalibration of powers between Parliament, courts, and devolved bodies.

>>> National dialogue about who we are, how we live together, and how we govern.

Because a nation without equal rights under law isn’t a democracy — it’s a patchwork of privilege and silence.

Who Should Engage With This Article

>>> Citizens concerned about fairness, representation, and justice.

>>> Legal scholars, constitutional experts, historians.

>>> Policymakers committed to reform.

>>> Anyone who believes democracy is a living system that must serve all — not just some.

Supporting Information

Media

Location & Impact Details

Vote To Help Prioritise Activity Listing

You must be logged in to rate.

Contact Details

There are no reviews yet.